Dorsal fin a pirate’s black sail

Here, and gone; here, and gone; here, and gone

Following seas eternally

Why are we sampling?

We are monitoring population recovery in both the resident killer whale ecotype (the AB pod) and the transient ecotype (the AT1 population), both of which suffered a significant number of deaths following the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989. These two killer whale ecotypes are separated based largely on genetics and diet preference—resident killer whales primarily eat fish while transient killer whales prefer marine mammals—and, despite the transient moniker, both groups are found regularly within the Prince William Sound and Kenai Fjords study area year-round.

As an apex predator, killer whales play a key role in the ecosystem through predation on fish and marine mammals. They are also a primary wildlife species of interest for viewing by the region’s vibrant tour boat industry. The tour boats provide not only a broad audience for the dissemination of our findings but also an opportunity to stress the importance of viewing guidelines and considerate behavior around the whales.

Where are we sampling?

This project is part of ongoing killer whale research in Prince William Sound and the Kenai Fjords region, Alaska. The overall study area stretches from the Nuka Bay, outer Kenai Peninsula region, to Cordova on the eastern edge of Prince William Sound.

How are we sampling?

The core objective of this project is the monitoring of population parameters based on photo identification. Additionally, we annually sample prey and fecal material to investigate feeding habits and map trophic changes. We have placed remote acoustic stations in ocean entrances frequently used by the whales to explore temporal and geographic patterns of use for both resident and transient killer whales. This is particularly valuable in winter when vessel work is not possible.

The types of analysis that result include population dynamics and modeling at appropriate intervals, genetic sequencing as necessary for determination of population affiliation, and acoustic analysis of remote hydrophone data. Genetic analysis of scats and of predation samples is conducted under cooperative arrangement at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, and Pacific Biological Station, Nanaimo, BC, Canada. Although work is focused on the southern Alaska resident and AT1 transient populations, which were both impacted by the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the study also includes the other two recognized populations in the region, the Gulf of Alaska transients and the Offshore killer whales. The project contributes annually to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service killer whale stock assessments. It also provides comparative data that is used in continuing studies of the endangered Southern Residents of Washington State. We actively collaborate with scientists at the NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center that direct research on the Southern Residents.

What are we finding?

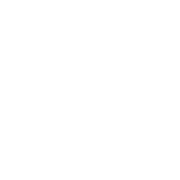

The AT1 pod of transients and the AB pod of residents were directly affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill and have not yet recovered to their pre-spill numbers. From 2017 to 2021, the AT1 population remained constant at seven individuals, below their pre-spill high of 22 individuals, and no further recruitment is expected due to the remaining females being beyond known reproductive age. The AB pod, after slowly recovering to a post-spill high of 22 whales in 2015, declined to 14 whales in 2017 and increased to 16 in 2021. This decline followed a marine heatwave during 2014-2016, which had acute and prolonged impacts on the Gulf of Alaska ecosystem and reversed 30 years of post-spill recovery for the AB pod.

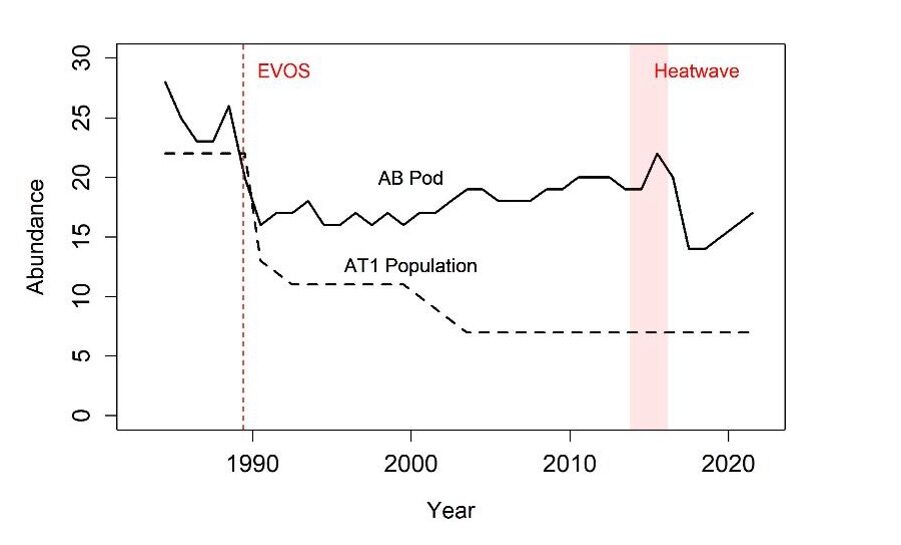

The scale/flesh dataset used in this study includes samples collected in Prince William Sound and Kenai Fjords between May and September from 1991 to the present. In the most recent study period, a total of 362 scale/flesh samples from at least 16 killer whale pods and 86 fecal samples from at least 8 pods were collected and analyzed for prey species identification. Chum and chinook salmon were identified as the dominant prey species in killer whale fecal samples from both Prince William Sound and Kenai Fjords. Other notable prey species included pacific halibut, arrowtooth flounder, coho salmon, sablefish, and sockeye salmon. These species were considered “major prey species” in the fecal dataset, detected in proportions greater than 1% in at least 4 samples. In the scale/flesh dataset, only chum, Chinook, coho, and sockeye occurred at these levels. Pacific herring, pink salmon, and steelhead had detections below 0.2% in fecal samples, and only one herring scale was found in the 245 scale/flesh samples, likely as secondary prey.

Locations mapped of scales/flesh from predation events (1991-2021; purple circles = Chinook salmon, orange triangles = chum salmon, silver squares = coho, red stars = sockeye salmon, green plus sign= herring). Pie charts show species fecal content of samples (2016-2021) collected in circled locations in Kenai Fjords (KF) and Prince William Sound (PWS) and during indicated time periods.

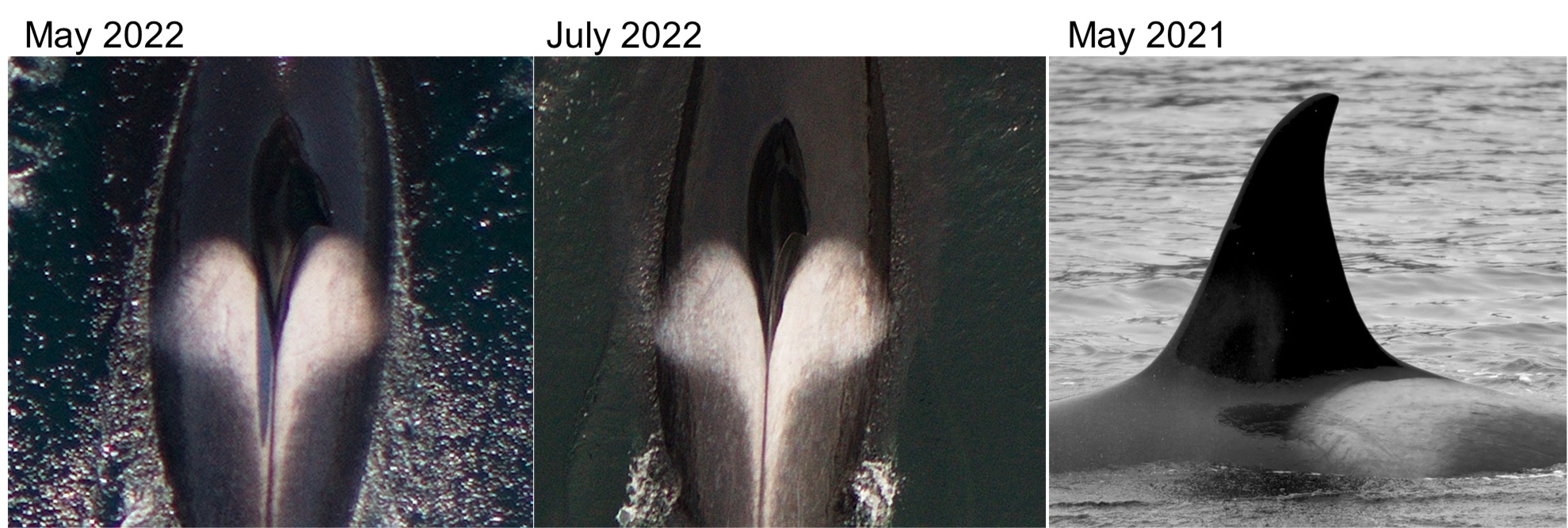

Recognizing the need to better understand nutritional health and the ecological factors influencing pod-specific population dynamics, we have integrated drone-based photogrammetry into our research for 2022. The ongoing collection of aerial images will contribute to quantifying length-at-age relationships for growth analysis and measuring body condition to infer nutritional health and pregnancies in killer whales. These metrics will play a crucial role in comparative analyses, allowing us to assess and compare the condition and size of different pods, evaluate the influence of female size on reproductive success, and monitor temporal changes in growth and body condition in response to environmental changes. Furthermore, we aim to compare the body condition and size of Alaska resident killer whales to other killer whale populations, specifically the endangered Southern Resident killer whales off Washington State, facilitating regular comparisons of the general nutritional health between populations.

Whales imaged by drone can be matched to our long-term photo-identification catalog using natural markings on their saddle patches. See the scars on the left side of AK9’s saddle, visible from both the aerial (left and middle, on two different days) and boat-based images (right). This allows measurements of morphology to be linked to whales of known age, sex and pod affiliation. We are using aerial images to measure length, body condition and pregnancy stats. These are sensitive indicators of individual health and, in combination, population status