Bubbles form curtain

net around prey from below

Is it a fluke?

Why are we sampling?

Where are we sampling?

We conduct two annual surveys: a 6-day survey in April each year and a 10-day survey in conjunction with the Gulf Watch Alaska winter bird and forage fish projects during late September. We focus our efforts on locations where whales have historically been observed foraging in Prince William Sound during the spring, fall, and winter (e.g. Montague Strait, Bainbridge Passage, Port Fidalgo, Port Gravina). The fall combined survey reduces vessel costs while increasing our knowledge of interactions among predators, prey, and habitat.

How are we sampling?

To determine if the whales were preventing herring recovery, we have to know how many herring are being eaten by whales. To answer this we need the number of whales are using Prince William Sound, how long do they remain in the Sound, and what are they eating. Whales can be hard to count because they spend so much time under water where they can’t be seen. We use the unique black and white pattern on the underside of their tail, or flukes to identify individual whales and come up with an estimate of abundance.

By photographing and identifying individual whales, we have created and continue to update a catalog of photographs of all the whales seen in our study. Knowing individual whales helps us understand their behavior, how long do they stick around the Sound? Do they have food preferences? Figuring out what they are eating can be tricky. We track the movements of each whale and determine what each whale eats, although it is difficult to find out what they were eating when they feed beneath the surface. We use a variety of techniques to identify whale prey, including jigs and nets to collect fish and krill near feeding whales and fish finders to distinguish zooplankton from fish. We also collect tissue samples from whales by means of a modified cross-bow to shoot a small stainless steel dart tip the size of a pencil eraser.

AN EXAMPLE OF PREY FROM AN AREA WHERE ACTIVE FEEDING OF HUMPBACK WHALES OCCURRED: EUPHAUSIIDS AND FORAGE FISH.

LIKE FINGERPRINTS, UNIQUE MARKINGS AND DISTINCTIVE TRAILING EDGES ON THE FLUKES ALLOW RESEARCHERS TO RECOGNIZE INDIVIDUAL WHALES.

During summers, local residents and boat operators provide reports of sightings and the Gulf Watch Alaska killer whale project contributes photo-identifications. These reports and photos are used to track whale movements and estimate the total number of humpback whales in Prince William Sound.

What are we finding?

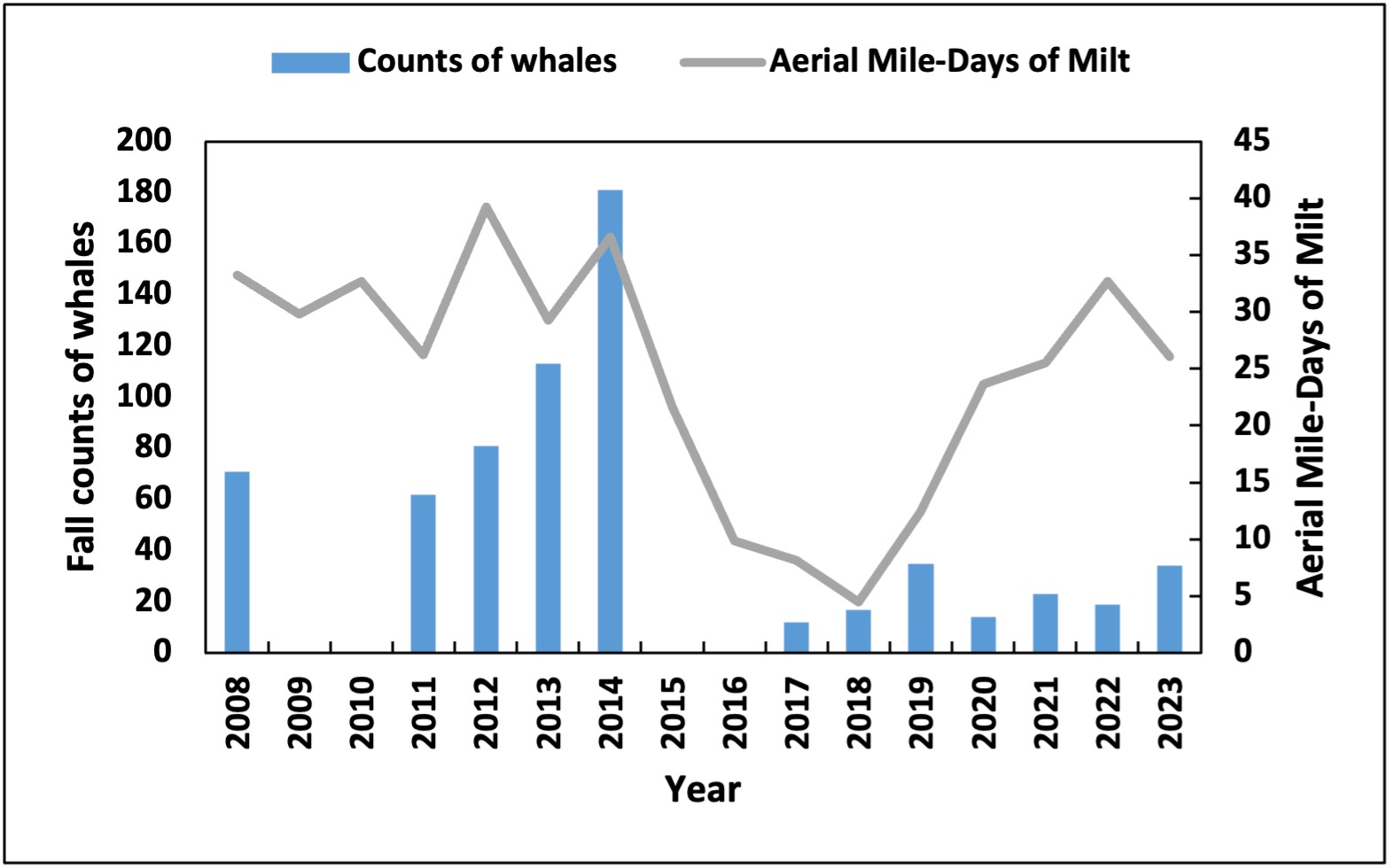

Fall and winter are important feeding periods for humpback whales in Prince William Sound. The whales may be eating 15-20% of the spawning herring, which is similar to the quantity removed by the commercial fishery prior to its management closure. While this level of predation is believed to be sustainable, many questions remain unanswered.

In December of 2014, shoals of overwintering Pacific herring and their predators failed to return to Port Gravina. The 2015 spawning event also proved to be unusual: we did not locate large shoals of herring, which are typical of the area in spring, and whales were targeting small, fast-moving herring schools.

This change in behavior and abundance corresponded to the 2014-2016 North Pacific marine heatwave (aka “The Blob). We also saw fewer calves and “skinny” whales during “The Blob” years. This suggests there is an issue with their prey. We know “The Blob” affected many species in the Gulf of Alaska, from plankton to birds and mammals. However, the impact on humpbacks seems to be lingering; as of 2023, both adult and calf numbers remain low. Did the whales move somewhere else to find food? Did they die from starvation? Continued long-term monitoring and collaboration with other research groups will help answer these difficult questions.

The relationship between humpback whales and herring biomass. Aerial-mile days of milt serve as a proxy for adult herring biomass. Herring data curtesy of PWSSC and ADF&G. (No fall surveys were conducted in 2009, 2010, 2015, and 2016).

You can check out the humpback fluke identification catalog showing some of the whales monitored under this program at: Prince William Sound humpback whale fluke identification catalog.